Why civil buy-in is essential to 21st century European defence policy

European security cannot only be built from the top down. It starts with people—citizens who are aware, engaged, and prepared. Civil buy-in and resilience are not secondary or symbolic; they are foundational to modern security.

Across Europe, unprecedented investments are being made in security and defence. Member states are revisiting their strategic compasses, increasing military spending, protecting critical infrastructure, and aligning more closely with NATO and EU allies. Yet, amid these top-down reforms, one crucial element remains underexposed: public engagement. More than ever, civil buy-in is essential for the effectiveness, legitimacy, and sustainability of European defence policy.

Citizens must be involved in two key ways. First, they need a basic understanding and literacy about their country’s security situation in order to effectively support or protest new policies. Second, they must become resilient themselves.

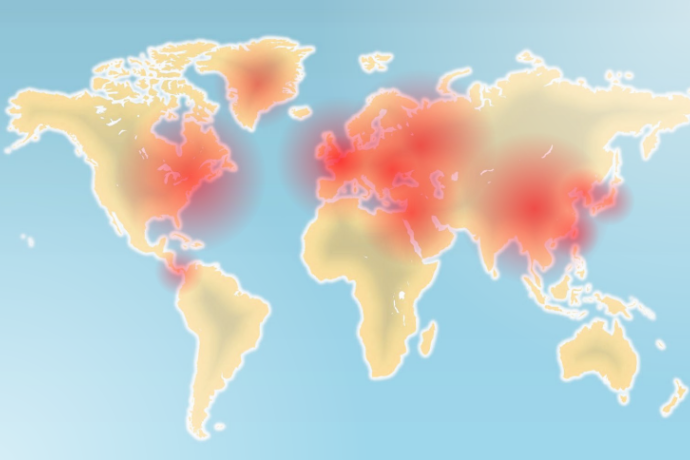

Modern threats are rarely purely military. Cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, economic coercion, sabotage of energy systems, and foreign election interference are all hybrid threats, and these target societies—not soldiers. In this context, traditional defence models are no longer sufficient. Secure societies must be resilient: socially, economically, psychologically, and institutionally.

That insight is gradually filtering into policy. Countries like Finland and Sweden already apply a ‘total defence’ approach, in which civilians, companies, governments, and civil society share responsibility for security and readiness.

The limits of a top-down approach

Defence traditionally operates top-down: policymakers decide, the public is informed, and agencies implement. However, this approach faces some fundamental challenges.

The first is democratic support. Defence budgets are rising fast—think of Germany’s Zeitenwende or the EU’s Readiness 2030. Without a clear public narrative and societal involvement, such investments risk being met with public confusion or distrust. Citizens want to know: why now, and what for? Civil buy-in helps anchor strategic choices in democratic legitimacy. Moreover, many defence decisions are made behind closed doors for security reasons. But where secrecy and democratic transparency collide, public trust becomes even more vital.

The second challenge is hybrid warfare. When elections are targeted by fake news or when hospitals are hit by cyberattacks, it’s not soldiers who respond first, but civilians, local authorities, and businesses. If they are unprepared, society remains vulnerable.

The third challenge is that critical infrastructure is largely civilian. Energy, telecoms, transport, and data networks are often owned or operated by private and local actors. Without their active role in planning, drills, and crisis communication, whole-of-society defence remains incomplete.

Finally, as a fourth argument, it is worth mentioning that, throughout history, major societal changes without mass support have typically ended badly.

So, what is resilience? What is this civilian buy-in?

The first step towards societies becoming more resilient is, of course, getting a clear idea of what resilience is. It has become a buzzword in EU policy, but it often lacks definition. Are we referring to hard measures like contingency plans, military mobility, crisis protocols, and infrastructure audits? Or to soft skills like media literacy, first aid, and community cohesion? Is resilience about mental toughness or logistical readiness? Or both?

This conceptual ambiguity makes it politically attractive—everything can be labelled “resilience”—but it also makes it dangerous. It risks diluting priorities; existing initiatives can be rebranded as resilience measures, while real investment lags behind. That’s troubling, especially considering NATO’s recommendation to dedicate at least 1.5% of GDP to civil preparedness. Without clear guidelines, the term risks becoming a semantic umbrella rather than a strategic tool.

If we want resilience to be more than rhetoric, it requires clear definitions, measurable goals, and political courage to prioritise. Otherwise, it will remain a popular word, but a missed opportunity.

Resilience falls into two main categories: personal resilience, or how individuals handle stress and adapt; and organisational resilience, or how systems or institutions stay functional and recover in times of disruption. In almost all member states, both kinds of resilience still need a lot of reinforcement.

Conclusion: Policy always starts with the masses

European security cannot only be built from the top down. It starts with people—citizens who are aware, engaged, and prepared. Civil buy-in and resilience are not secondary or symbolic; they are foundational. A defence strategy that ignores the public will lack legitimacy, traction, and long-term impact. To face 21st-century threats, Europe must invest in a whole-of-society approach that makes security a shared responsibility.

Policy doesn't begin in boardrooms or ministries. It begins with the masses.