How to lift Von der Leyen’s curse

‘We all know what we have to do, but we don’t know how to get re-elected once we’ve done it.’ Thus spoke Jean-Claude Juncker as then President of the Eurogroup back in 2007. Fast forward to 2025, Europe’s new ‘Juncker curse’ is that its politicians know what they have to do but don’t know how to pay for it. Call it Von der Leyen’s curse.

No fewer than three major reports on the future of the European Union – Letta on the internal market, Draghi on competitiveness and Niinistö on economic and civil resilience – are urging European leaders to push full steam ahead, with deepening market integration, with boosting innovation and investment in critical sectors and technologies, and with building self-reliance to face crisis and conflict. Never before has so much European political and economic federalization been urged by so few for so many.

Never before has so much been expected from European coffers as well. Europe’s quest for prosperity, strength and security comes with an unprecedented price tag. Draghi alone is advocating for an additional 800 billion euros in spending per year, almost four times the total annual commitments of the European Union in 2024. How on earth is Europe supposed to cough this up? And how can spending on this scale by mobilized to support common EU priorities over merely national preferences?

Massive public-private partnership schemes

The most elegant solution would be massive public-private partnership schemes. The long standing and always delayed ambition for a truly European capital market shall now focus on a ‘savings and investment union’ to pool resources from fragmented European capital markets for strategic EU-wide investments. This requires the confluence of three forces: schemes and vehicles to direct, bundle and scale available investment capital, grand scale projects that offer attractive return potential, all enabled by deliberate ‘made in Europe’ industrial and technological protectionism. Airbus is the historic example that comes to mind. Space infrastructure, including the recent €10.6bn Iris² satellite deal to rival Elon Musk’s Starlink in Europe, is another live European initiative. However, achieving such triangulation and turning it into shovel-ready projects at scale presents tremendous challenges as member states typically understand ‘made in Europe’ to be made in their respective countries at minimal investment risk.

In the ideal scenario the European Union, together with the European Investment Bank, will offer institutional investors and venture capitalists offers they cannot refuse: the ability to claim a stake in the economic and technological future of the continent – whether it is in defence, semiconductors, biotech, AI, telecom, energy infrastructure and the like – with guaranteed government spending and/or protected market potential as a revenue model. Coordinating this from Brussels across 27 member states seems implausible. Just consider how the much simpler common ‘European war bond’ for shared defence capabilities and production has failed to materialize even amidst the horrors in Ukraine.

Then there are taxes. A European Union that raises import tariffs, emission levies and other taxes to make the playing field fair and sustainable in the European market can potentially invest tens of billions annually. However, taxes may be counterproductive if they hurt the very European industry we seek to keep and protect – just see how the current Green Deal is generating greening through deindustrialization. They may be downright destructive if they end up hurting companies from countries with which Europe does not want a trade war. Think of the US under Trump, for instance. A carbon border adjustment tax – one intended source of future EU tax revenue – hurting US imports into Europe will simply spell US tariffs at the other end. A clean taxation solution would be a small general EU tax paid by European citizens or families. This would generate much more financial firepower while making the Union's survival mission tangible for every citizen. Clean and democratic, but politically wholly inconceivable. Maybe existing EU resources could be redirected towards new EU priorities during the next EU budget cycle – say less subsidies for farmers and more for industrialists. That promises to be a heck of a political tussle stretching well into 2027 – too little, too late.

Just when major public investments are required, the stability of Europe’s unfinished monetary union once again imposes preventive budgetary discipline on Member States

What is left are debt mechanisms, usually politically very conceivable indeed. However, just when major public investments are required, the stability of Europe’s unfinished monetary union once again imposes preventive budgetary discipline on Member States. Deficits for strategic investments remain possible but require country-by-country negotiations with the European Commission. At the end of that process, national state support awaits, often too small-scale and also problematic as a distortion of free and fair competition between European countries. The EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund also exists as a mere distribution centre for national spending plans. European mutualized debt invested directly from Brussels, that is yet another political Rubicon the Member States still have to cross. Dito for the European Commission bundling and steering national subsidies towards common European investment projects.

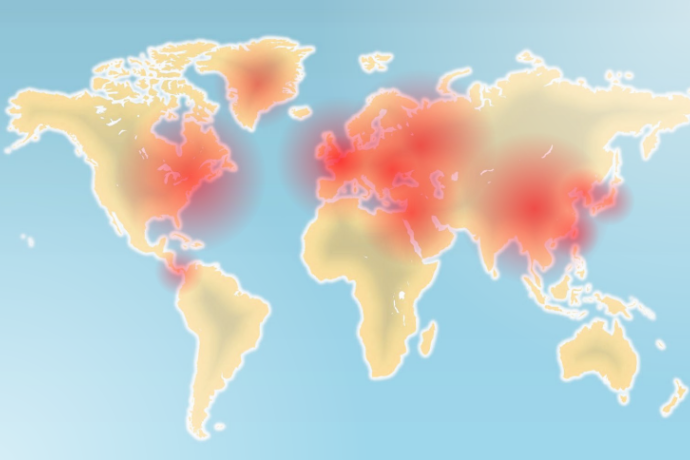

Europe not only has too few resources, it also does not know how to spend these quickly and efficiently. EU processes are slow, bureaucratic and generally not very transparent for the participating companies or countries. Individual countries can switch more quickly when the pressure is high – inside and outside Europe. The European Union must compete with China, Russia and the USA in what has become a global arms race of state capitalism and mercantilism. But Brussels has neither the political nor the financial heft to compete with Beijing, Moscow or Washington.

If the European Union really wants to live up to its ambitions, it must be able to invest and partner swiftly from Brussels in and for companies or business clusters. The existing platform for Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) can be a stepping stone, provided it can scale up and speed up. More likely is an ecosystem of investment initiatives and vehicles outside formal EU programmes, through coalitions of investors and/or member states responding to and enabling the industrial policies from the EU.

First mover advantage will play a role as countries with a stake in strategic sectors can step up and claim future market share by contributing to collective EU ambitions. A country like Poland has been leading the pack in mobilizing public spending and other member states for defence and security capabilities along Europe’s eastern border and in the Baltic. Haunted by the spectre of Donald Trump returning to the White House, a multinational €500bn defence fund initiative is now being considered by willing countries inside and outside the EU, potentially including the UK, to be enabled by the European Investment Bank as well (as reported in the FT of Dec 6).

This, then, is the way to lift Von der Leyen’s curse. Allow coalitions of states to combine in respective self-interest and in strategic partnership with their industries, taking state aid to a coordinated multinational level, while steering and enabling them through EU-institutions towards common EU-goals. Forget the old separation of the European market and domestic state aid: the latter serves the integration of the former for geopolitical purposes. Forget the decision making machineries that often stymie EU-action: create room for flexible ad hoc arrangements within the overall EU strategy. Forget even the distinction between member states and third countries: what matters is the right geopolitical coalition in support of EU policies, and that includes a country like the UK in matters of security and defence. Lifting Von der Leyen’s curse, it turns out, can also lift the Brexit curse.